Programme

|

FRIDAY |

||

|

9:00–10:45 |

Opening |

|

|

Barry Loewer |

||

|

Peter Rauschenberger |

||

|

10:45–11:00 |

coffee |

|

|

11:00–11:45 |

Ferenc Huoranszki |

|

|

11:45–12:00 |

coffee |

|

|

12:00–13:30 |

Keynote: Howard Robinson |

|

|

13:30–15:00 |

lunch |

|

|

15:00–16:30 |

Martine Nida-Rümelin |

Conscious Beings as Perfect Individuals: Arguments from Counterfactual Thought |

|

Philip Goff |

A Conscious Universe versus a Universe Grounded in Consciousness |

|

|

16:30–17:00 |

coffee |

|

|

17:00–18:30 |

Daniel Kodaj |

|

|

Barry Dainton |

||

|

20:00 |

Conference Dinner |

|

|

SATURDAY |

||

|

9:30–11:00 |

Tim Crane |

|

|

David Pitt |

||

|

11:00–11:30 |

coffee |

|

|

11:30–13:00 |

Hanoch Ben-Yami |

When Howard Took-off His Glasses, and Other Sensational Incidents |

|

Katalin Balog |

||

|

13:00–14:30 |

lunch |

|

|

14:30–16:00 |

Dean Zimmerman |

|

|

Katalin Farkas |

||

|

16:00–16:15 |

coffee |

|

|

16:15–17:45 |

István Bodnár |

|

|

Penelope Mackie |

||

|

17:45–18:00 |

coffee |

|

|

18:00–18:45 |

David Papineau |

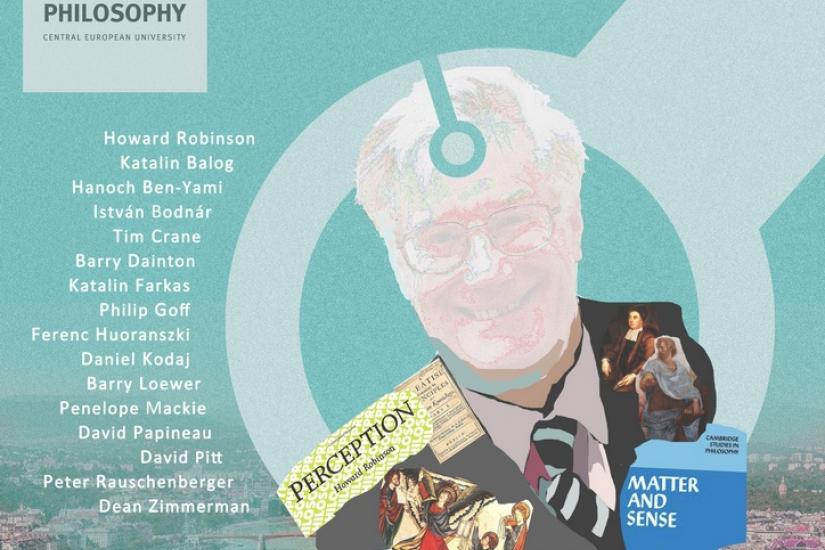

AbstractsFrom the Knowledge Argument to Mental Substance

Howard Robinson

My book, From Knowledge Argument to Mental Substance: Resurrecting the Mind, Which is due to appear with Cambridge University Press in February, is largely, but not wholly, based on work in the philosophy of mind that I have published in the last twenty-five years. Much has happened since CUP published my Matter and Sense in 1982, and many sophisticated physicalist and semi-physicalist theories have been developed. It is one of the arguments of this book that this sophistication only disguises the fact that no serious progress has been made: the lucid but inadequate theories of J. J. C. Smart and D. M. Armstrong still remain the best that standard physicalism can achieve.

This book divides into three parts. In Part I, I argue against all the main attacks that have been made on the Knowledge Argument, but, beyond that, I argue that the Knowledge Argument does not merely resist all attempts to refute it, but that is has much more powerful consequences than is usually allowed for by either side in the discussion. What it shows is that the qualitative dimension of reality, without which the world can be nothing more than a bare formal system, is something that standard physicalism cannot accommodate. If the knowledge argument were not correct, there could be no manifest image of the world at all, and without the manifest image, there could be no scientific image either. I also try to prove the inadequacy of various non-reductive naturalist strategies, such as neutral monism and those that derive from the work of Wittgenstein and Donald Davidson.

In Part II, I challenge one of the main motivations of physicalism. The physicalist believes in the closure of the physical world. It is a consequence of this that, if the mental is not physical, it must be epiphenomenal. I try to show that if the world is closed under physics – that is the physical world’s most fundamental and microscopic level - then all higher levels, which must include the brain/mind if physicalism is true, will be epiphenomenal: I defend, that is, a version of what Kim calls the exclusion principle, and I do this via an investigation of reductionism and semantic vagueness. I carry the conclusion further and argue that there are no strict physical individuals at all: at most there are quality placings in space-time, presumably as the features of events.

In Part III, I try to prove that we must be simple immaterial selves, and as such, minds are the only true individuals in the natural world. In the final chapter I tie this thought up to themes in the history of philosophy. I argue that a doctrine universally ignored by analytical philosophers, namely Plotinus’s doctrine of the One, can be used to throw welcome light on the notion of an individual and on modern debates concerning the unity of substances. In fact, the notion of individuality that we project on the world has its source in our own identity as individuals. In this way, Plotinus’s metaphysics and Humean conventionalism are both true. In the process, I draw attention to a striking – and, as far as I know, unnoticed - parallel between, Frege’s treatment of concepts, and Aristotle’s criticism of Plato’s theory of forms, and how this supports a form of neo-Platonism.

In my paper, I shall expound some themes from the book, especially my reasons for thinking that the knowledge argument is stronger than people seem to imagine, but will look into other features of it, on request.

Katalin Balog

In this paper I discuss three problems of consciousness. The first two have been dubbed the “Hard Problem” and the “Harder Problem”. The third problem has received less attention and I will call it the “Hardest Problem”. The Hard Problem is a metaphysical and explanatory problem concerning the nature of conscious states. The Harder Problem is epistemological, and it concerns whether we can know, given physicalism, whether some creature physically different from us is conscious. The Hardest Problem is a problem about reference. It is the problem of explaining how, given physicalism, phenomenal concepts are able to refer, determinately, to physical/functional states of the brain. In this paper I explore how these three problems appear from the perspective of a physicalist approach to consciousness based on Brian Loar’s account of phenomenal concepts, recently dubbed the “phenomenal concept strategy”. My contention is that this approach can go quite far in handling not just the first two problems but the Hardest Problem as well.

When Howard Took-off His Glasses, and Other Sensational Incidents

Hanoch Ben-Yami

I discuss a variety of cases of illusion and hallucination that have been taken to support a representational theory of perception: blurred vision, after images, dreams and others. I try to show that they can be explained while maintaining a direct perception view. If successful, this eliminates the so-called hard problem of consciousness.

FINAL CAUSES IN ARISTOTELIAN DEMONSTRATIONS

István Bodnár

Aristotle does not present his natural philosophy and science in an axiomatic fashion. Nevertheless, according to the Posterior Analytics scientific knowledge should at least in principle be amenable to axiomatic presentation. In my talk I will concentrate on a crucial detail where the fit between scientific practice and the Analytics is even more problematic. Aristotelian philosophy of nature and science deploy teleological considerations, often formulating claims of the form that something has a property, something is the case, because that way it is good, or that way is the best possible for it to be, or to reach its natural goal. Such claims are claims about the causal efficacy of a goal.

Scientific explanations, as the Posterior Analytics submits, should formulate demonstrations where these demonstrations prove their conclusion by means of the cause of what is expressed in the conclusion. All four kinds of causes should be involved in such demonstrations. Nevertheless, the example Aristotle gives for the use of final causes in demonstrations is problematic: either it is not an instance of a final cause at all – instead it could be an instance of a teleological relation between an efficient cause and its goal, where the demonstration will start out from the efficient cause – or even if there is a pointer towards a demonstration through a final cause, that will rest on another syllogism, starting out from the efficient cause. Accordingly, both of the options would demote, or at least restrict the use of final causes in scientific demonstrations.

After this I will turn to Aristotle’s scientific treatises, both the actual explanatory strategies he deploys, and the theoretical considerations about the status of final causation. I will argue that here again we find a somewhat restricted use of final causes – which, however, is bolstered by theoretical considerations about the intimate relationship between efficient causes, forms and goals.

Tim Crane

Howard Robinson has written illuminatingly about the relationship between thinking about particular objects as such and having a general conception of these objects. Robinson argues that those (like me) who take intentionality as a primitive or basic fact about the mind fail to recognise the significance of this distinction. In this talk I argue, against Robinson, that having a general conception of an object is as much a manifestation of intentionality as so-called 'singular' thought is, and that Robinson therefore really belongs with those who take intentionality as primitive. In addition, I offer a diagnosis of why Robinson sees the matter differently, and I criticise the assumptions he seems to be making — assumptions which, it seems to me, obscure the real importance of his views on intentionality.

Barry Dainton

Of all the problems confronting the traditional theist, the problem of natural evils (earthquakes, diseases and the like) is among the hardest. Wouldn't an all-powerful and benign God be capable of arranging things a little (or even a lot) better? For anyone who is prepared to accept the possibility of computer-generated or computer-controlled consciousness a potentially appealing solution to this problem is available. If this world is a virtual reality that is created and sustained by non-divine programmers, it is the latter who are directly responsible for the natural evils we encounter, not God. I will be arguing (a) that this solution is more compatible with traditional theism than it might initially appear, and (b) that it provides the theist with a compelling reason to adopt a version of idealism.

Katalin Farkas

In his book Perception, Robinson states that “qualia are close cousins of sense-data”. This talk investigates the similarities and differences between positing sense-data or qualia in a theory of perception.

A Conscious Universe versus a Universe Grounded in Consciousness

Philip Goff

Howard Robinson’s forthcoming book From the Knowledge Argument to Mental Substance presents a wide-ranging and rigorous defence of Berkeleyan idealism, the thesis that facts about the physical universe are grounded in facts about mental substances. One crucial move in this argument is the rejection of panpsychism, which Robinson construes as the ‘smallist’ view that the fundamental facts concern conscious subjects at the micro-level. However, there is an alternative way of construing panpsychism: cosmopsychism, the thesis that all facts are grounded in facts about the conscious universe.

I will argue that cosmopsychism is coherent, and that it offers a more elegant and empirically plausible form of anti-physicalism than Berkeleyan idealism. I will also suggest a way for the cosmopsychist to defuse Robinson’s argument that human minds are fundamental substances.

Ferenc Huoranszki

In Matter and Sense Howard Robinson argues that fundamental properties must be qualitative in the sense that they are not pure powers or properties the instantiation of which depends on such powers. His argument rests on two premises. According to the first premise, every real object must possess a determinate nature. According to the second, the nature of any power P is given by what would constitute its actualization. In this talk I shall argue that, despite their distinguished Aristotelian pedigree, the truth of these two premises is not beyond dispute. Hence, qualitative properties need not be ontologically more fundamental than powers are.

Why (and why not) be a Quantum Idealist

Daniel Kodaj

I’ll argue for the thesis that the quantum state encodes the potential experiences of immaterial minds. The advantages of this view with respect to both (latter-day) Everettianism and the de Broglie/Bohm theory will be highlighted.

Barry Loewer

I will explain how a proposal for a fundamental physical theory of the universe that explains why the second law of thermodynamics holds also provides an account of counterfactuals that avoids certain difficulties that beset David Lewis’ famous account. I will then go on to show how this proposal can provide a novel response to Peter van Inwagen’s famous argument that determinism and free will are incompatible.

Penelope Mackie

It is widely held that, in holding physical objects to be mind-dependent, Berkeley is in conflict not only with common-sense beliefs about the physical world, but also with the common-sense conception of perceptual experience. In this paper I explore the possibility of defending Berkeley against this charge by questioning whether the common-sense conception of perceptual experience really includes anything inconsistent with Berkeley's theory.

Conscious Beings as Perfect Individuals: Arguments from Counterfactual Thought

Martine Nida-Rümelin

Howard Robinson argues for substance dualism on the basis of considerations concerning counterfactual circumstances. I will present a similar argument which relies on the same intuition. In the talk I will argue that this intuition is deeply incorporated in our thought and that there is reason to trust the intuition as adequate to the nature of conscious beings.

The Plausibility of Representationalism

David Papineau

A representationalist theory of sense experience can seem plausible at first sight, but at bottom it involves eccentric metaphysical commitments. In this paper I shall first expose these commitments, and then offer an account of why they seem plausible despite their oddity.

How do Thoughts Find Their Objects?

David Pitt

Causal/informational theories of intentionality build a connection between thought and its objects into the very notion of content. Concepts are individuated by the object(s) or property instantiation(s) whose presence is lawfully causally correlated with their occurrence, and thus acquire their contents and their referents simultaneously.

But causal theories have problems with indeterminacy. There is Quine's problem, which arises out of what I’ll call causal superposition; there is the disjunction problem, which arises out of what I’ll call causal spread; and there is the stopping problem, which arises out of what I’ll call causal depth. In all cases, there are multiple candidates for content determiner/referent, and no obvious way to choose among them derivable from the basic machinery of the theory.

While causal/informational theorists have expended considerable effort and ingenuity in the search for a solution to these problems, other philosophers have proposed that causal relations be replaced with qualitative features of experience as determiners of content. The concept HORSE, for example, has the determinate content horse, and not the indeterminate or disjunctive content horse or undetached-horse-part or horse-phase or cow-in-the-mist or horse-picture or horsey retinal display or horsey thalamic neural assembly or ..., and thus refers to horses, because of its intrinsic cognitive-phenomenal, descriptive character.

However, if the causal approach is abandoned, its advantage of a fundamental, constitutive connection between content and reference goes with it, and some other account must be given of how thoughts get to be about thought-independent things. In my talk I will attempt to show how this can be done.

Peter Rauschenberger

'The dogma of PC', PC being the thesis of physical closure, is a phrase that occurs in Howard Robinson's new book (p. 59). The context in which it occurs is the reconstruction of the reasons Frank Jackson gave for abandoning the knowledge argument in 'Postscript on Qualia' (1998) and 'Mind and Illusion' (2004). Belief in PC forces one to make a choice between embracing epiphenomenalism or abandoning the knowledge argument. In Robinson's reconstruction, Jackson abandoned the knowledge argument because he changed his mind about the respectability of epiphenomenalism, PC being the fixed point of his thinking. Robinson's assessment of whether the epistemic standing of PC justifies such a philosophical apostasy is expressed by dubbing PC a dogma.

David Papineau's stance on the epistemic standing of PC is in stark contrast with Robinson's. In 'The Rise of Physicalism' (2001) he wrote in relation to PC "I see no virtue in philosophers refusing to accept a premise which, by any normal inductive standards, has been fully established by over a century of empirical research", while noting that "there do exist bitter-enders of just this kind". I hereby propose to establish the Guild of Bitter-Enders regarding PC, and this paper I offer as a contribution towards its manifesto.

Vague Objects and Precise Selves

Dean Zimmerman

Howard Robinson and I both find it problematic to identify a person with a vague object. We agree that all the sensible physical candidates for being a person are vague, and reach the common conclusion that we are immaterial thinking things. We take rather different routes from vagueness to immateriality, however. I criticize his path, commend my own, respond to an objection from Penelope Mackie, and make use of some of Robinson's thoughts about embodiment in defense of substance dualism.

Poster

Download the high quality printable poster here.